Essay: The treasure inside my grandma’s jewelry box

After her funeral in 2011 we opened her jewelry box. We found her watch, several copper bracelets to help with arthritis, tiny rings the circumference of a nail’s head, all different, with the birthstone of each grandchild.

The jewelry paled in comparison to what I discovered next.

–

A couple of decades earlier, my grandma’s brain aneurysm burst for the first time.

A cutting-edge balloon technique stopped the bleeding and saved her life. For a while, her vision suffered. She couldn’t see the ring my parents came to show off after getting engaged. Eventually she made a full recovery.

I knew none of this growing up, spending most weekends between both sets of grandparents’ houses in eastern Iowa.

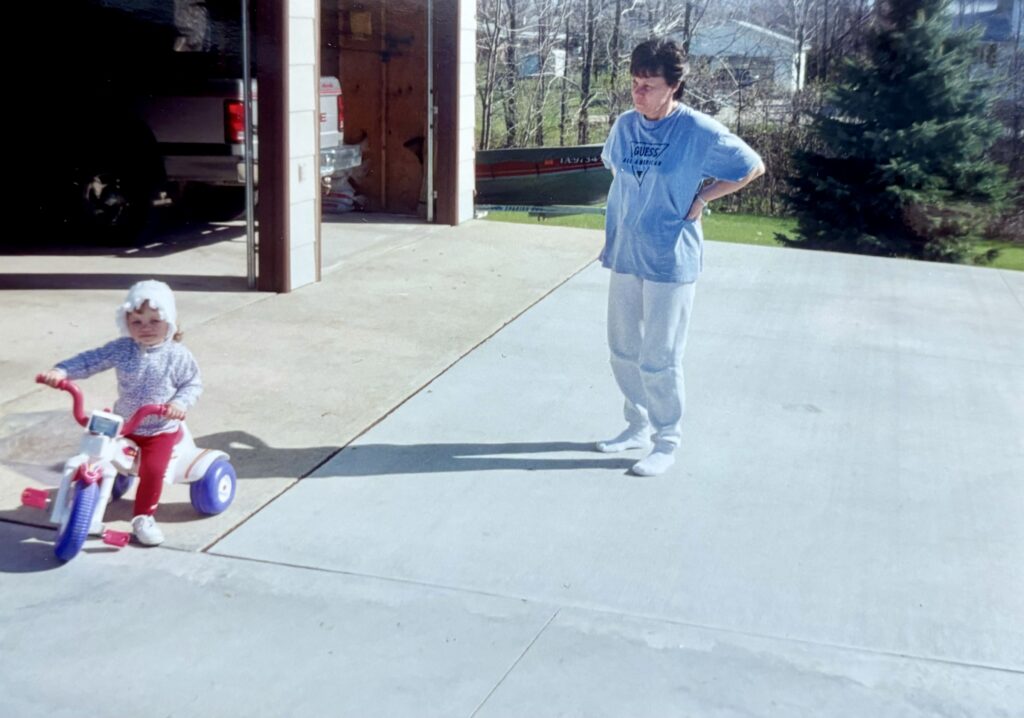

What I knew was my grandma poured the ingredients for pancakes into a glass mixing bowl so I could stir the batter with a wooden spoon in the wee hours of the morning. She allowed my sister and me to dip a comb in water so we could slick her short, dark hair back and then gather it into a dozen small brightly colored hair ties. She strolled down to the park with us, pounded the fake drums in the Christmas play I directed all my cousins to participate in, cut my hair and rode bikes with us. She always participated, never on the sidelines.

My maternal grandpa died when I was 2, before I could really remember him. My paternal grandpa died of lung cancer in January of 2006, when I was in the fourth grade, and then that summer, my maternal grandma died unexpectedly. Their passings left gaping holes in our lives, particularly on the weekends and holidays. They opened my eyes to the inevitable: Life can be gone in an instant.

Yet, somehow I felt this could not apply to my grandma, the last remaining grandparent. She was perfectly healthy, meant to live forever.

But being healthy doesn’t always stop your body from betraying you.

After the aneurysm was fixed, the doctors told her she didn’t need to be regularly checked. They believed at the time that she was as likely as anyone out on the street to have another one bleed. That is to say, unlikely. Or so they thought.

Advancements in the field revealed that it is possible that those who’ve had one brain aneurysm have about a 20% chance of having one or more others. But the doctors who operated on her never informed her of the new science and that she should be seen regularly to ensure there were no more lethal landmines in her skull. So she wasn’t.

The ticking time bomb detonated in 2011. She now lay unconscious at the University of Iowa hospital, the beep of the monitors hooked up to her the only sign of life. I had no idea whether she could hear me tell her about the Hawkeyes men’s basketball game against Purdue. Or that I loved her.

–

After we ate hospital food for days, Old Chicago’s pepperoni pizza deserved five Michelin stars. My grandma’s best friend, Mary, had stayed back in the hospital room while our family went out. As we finished eating, my aunt’s phone rang: She was awake.

We rushed back to find her still motionless, eyes shut. She couldn’t speak, but if you asked her a question, she could squeeze your hand. “Do you want me to stay here with you tonight?” Mary asked. Squeeze.

Doctors didn’t have the science to explain the moment of consciousness with such limited brain activity. Maybe it was just a coincidence. Or maybe my grandma woke up to hear our goodbyes.

–

At the bottom of one of the jewelry box’s drawers, she’d tucked a piece of notebook paper. It had been folded in half, and then thirds.

Unfolding it, I recognized the curvy penmanship with monkey tails on almost every letter. My handwriting.

I dated the letter March 20, 2009, at 9:54 a.m., two years earlier. I wrote that I’d just gotten my first cellphone and that my older sister was still sleeping — go figure. I told her I’d just joined the track team and I was no good at sprints. I ended it with, “Hope to see you soon.”

The contents of the writing were nothing extraordinary, yet it had meant enough to her to keep it.

If she hadn’t heard me in the hospital, this was my confirmation. She knew how much I loved her, and I knew she loved me.

The letter is stored for safekeeping, in the bottom drawer of my jewelry box.