As told to Emily Kestel

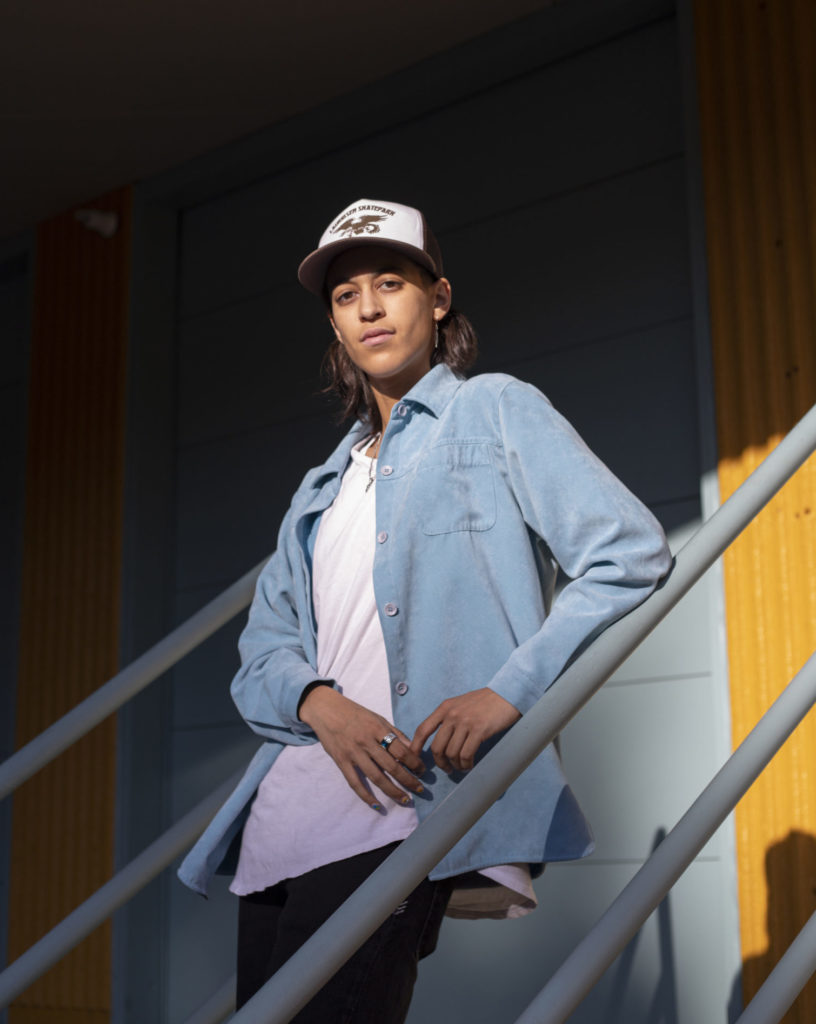

Jo Allen is a nonbinary entrepreneur who started their photography business, Jovisuals, primarily as a way to help LGBTQ people feel valued, empowered and visible. In 2016, they were diagnosed with stage 4 non-Hodgkin’s Burkitt lymphoma. Allen also works as a communications fellow with Future Leaders in Action. They live in Des Moines.

The following story has been formatted to be entirely in their own words, and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

As a kid, I was what the world wanted me to be. In terms of identity, my expression was compromised because not only was I living in a place where everyone looks a certain way, I was also in a house where comments were made if I wore boy-like clothing. I’m a person of color in a very white area, so either you try to fit in or you stand out. I was more scared of standing out than fitting in, so I chose to fit in rather than embrace myself and my identity.

The moment I went through cancer, it allowed me to reexamine my identity, my purpose – everything.

I was five weeks into my freshman year of college at the University of Northern Iowa when I was diagnosed. It was at such a pivotal moment in my life. I was a bird ready to leave the nest and live my best life. At that age, you’re just trying to be a kid. You want to make friends and go out and do things. I couldn’t even do that because my symptoms were so bad. I didn’t know what was going on and I was all alone in a space that I didn’t know how to navigate. I was very depressed. I would sleep a lot. Not only did I not want to leave my room, but I also couldn’t physically leave my room because I was so weak.

I felt symptoms six months before I got diagnosed. On my 18th birthday, I went out to lunch with my mom and my back started hurting to the point where I was crying. I couldn’t sit in a chair comfortably. It turns out my back was fractured. I carried that pain throughout the summer. I was working at Journey’s and I was sitting down with a heat pack on my back because it hurt to stand or bend over. I couldn’t shave my legs because it hurt. I would have to call my friends and say, “Hey, can you walk me to the bathroom,” because I would have to use the wall for assistance. Nobody knew what was going on. I kept deteriorating further and further. I went from being 125 pounds to being 98 pounds.

When I went to urgent care, they said that they couldn’t test me for the things I needed to be tested for, and that I needed to get into an ambulance. It was so dramatic.

I didn’t know what stage 4 meant. I just knew that it was everywhere and that it wasn’t good. I didn’t know that I only had 48 hours to live until way later.

I had to get the most aggressive chemo that you had to get. I had to drop out of college because every 21 days I would have to go to the hospital and stay there for five or six days for my round of chemo. I did that for nearly six months. I dropped out, went back to UNI that fall for two years and then transferred to Iowa State in 2019.

During cancer, the most important thing to me was my hair. I was so upset about losing my hair. It was down to my belly button. It was losing a part of my identity. It was like a security blanket.

I connected hair to being perceived as a woman. It was a thing that I thought made me attractive and made me look like who I was supposed to be. I was afraid of how I would look attraction-wise. Obviously, with chemo, you don’t look cute, you don’t feel hot. You look like a boiled egg.

I remember one thing my dad said to me at that time. I was crying and I said that I didn’t want to lose my hair. He said, “I’d rather have you alive and here with no hair than you buried with all your hair.” At that point I had to say to myself, “It’s simply hair.”

After I started my first round of chemo, my favorite nurse told me that I was going to lose my hair in a week. She was right. A week later, all of a sudden I started noticing a decent amount of hair falling out. I had naturally curly hair, so I couldn’t brush it. Because I couldn’t brush it, it had matted up. It had gotten to the point that I had to shave my hair off because it was a clump of hair on the top of my head, and if I were to brush it, I would risk pulling out more of my hair. That week, we got to the hair salon and I got my hair cut. It took 27 minutes. That’s what my ex always said: “I held your hand for 27 minutes while you lost your hair.” I was crying. My identity was being taken away from me. I couldn’t hide behind my hair anymore.

Cancer for me was the moment I got to change who I was. There was a big fear of me dying and never fully being honest about who I was. I knew I was gay around the age of 15. By junior and senior year of high school, I was coming out to close friends and teachers that I was close with and could trust. I didn’t come out to my family until later. I was raised Catholic. So that intersecting identity of being Catholic and Black, where we don’t talk about queer people around here, that was hard.

I told my sister first. My brother was too young to understand. My mom had always supported queer people, so I already knew that she wouldn’t care. It was my dad that I was the most afraid of telling.

I came out to my father during my first round of chemo because I didn’t know if I would make it. And what’s the worst thing he could say? I’m dying at this point.

I said, “Dad, I’m gay.” I was crying because there was this fear that I’ve been taught to not be that person, that this was deviant and not acceptable.

His response was good for me dying and putting that on him like that. He told me that he had known about the girls that I dated and that he supported and loved me. He said that he accepted it, but I don’t feel it. I don’t think he fully knows how to show love to me.

To be in the position where cancer is forcing me to reveal my identity, that was a lot for me. It still is. You want your identity to be celebrated and to feel like you have your parents’ support.

Cancer made me have to build up my self-confidence again because looking at myself in the mirror, I saw skin and bones and sunken eyes and no hair. I looked like a lifeless human being. Finding ways to express myself in the hospital was really important to me. I stopped wearing the hospital gowns, I was over it. I started wearing comfy, cozy flannels and button-downs.

I grew my hair out, but at that point I looked like a Q-Tip. My hair was just floofy. I got it chopped five months in and I got a short haircut. That was my first masculine haircut that I could get on my own terms.

I have never grown my hair out to my pre-cancer length, and I don’t know if I ever will. But I’m currently growing my hair out to shave it off for my five-year anniversary. I want to be able to do it on my own terms.

When I look back on that time, I’m proud of how I handled it because that’s a lot to go through in a very short amount of time. In that life or death moment, I chose to start fully expressing and welcoming who I was instead of hiding it to please others. It gave me the drive to accept myself and to find a way to help others accept themselves and feel comfortable.

I hated cancer. It was terrible. But in terms of the outlook that it left me, I’m happy I went through it. I’m at a place where I love who I am. Am I comfortable in my body yet? No. I don’t think many trans or nonbinary individuals feel comfort in their body most times. It’s a work in progress.