By Emily Kestel

Say you’re in an all-staff meeting the day after a poor quarterly sales earning report comes out. The mood in the room is tense, but nobody’s mentioning it, preferring instead to focus on the sales team’s wins in hopes of boosting morale.

Or maybe you’ve got a meeting scheduled with your boss about a new project you’ve been assigned to work on, but just last week she denied your request for a raise. You don’t want to bring it up again because you don’t want to make your relationship more uncomfortable than you already perceive it to be.

Perhaps you and your partner have a mountain of debt to pay off, but you both choose not to acknowledge it with each other because you know that doing so will likely cause an argument.

Maybe your co-worker always comes into the office smelling like a pile of dirty socks, but no one wants to tell him because they don’t want to offend or embarass him.

All of these situations have a common denominator: Everybody knows it, but nobody is talking about it.

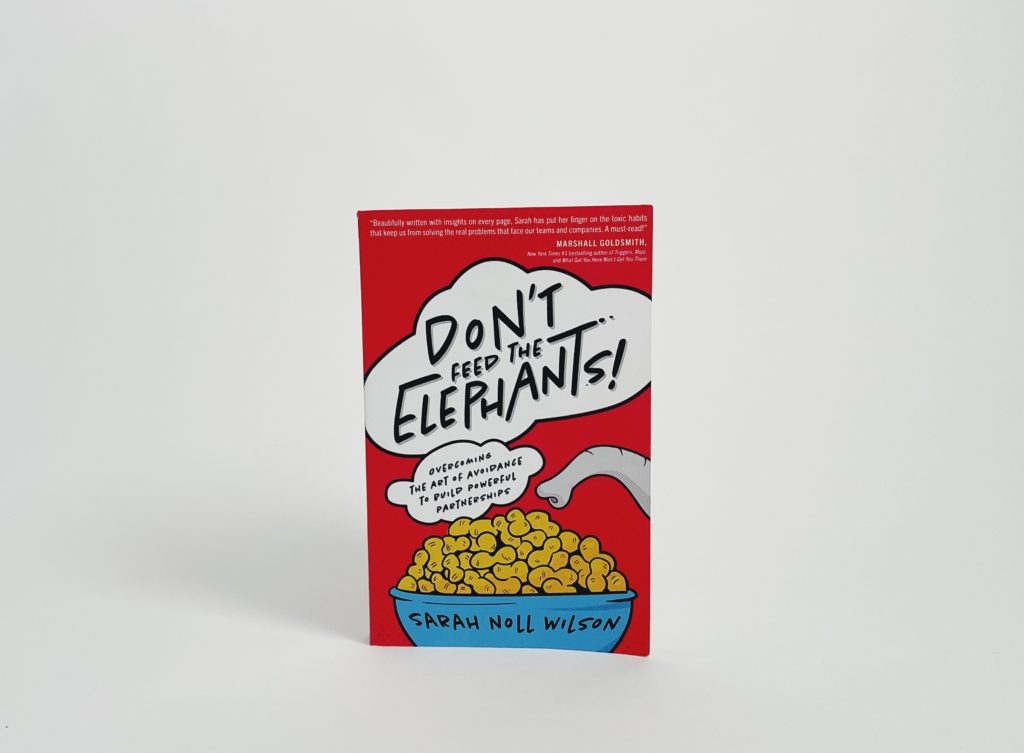

In “a love letter to my fellow avoiders,” executive leadership coach Sarah Noll Wilson expanded on the common American idiom of “the elephant in the room” in her first book, “Don’t Feed the Elephants!: Overcoming the Art of Avoidance to Build Powerful Partnerships.”

While an elephant in the room may be caused by a person or process, the actual elephant is not the noun in play – it’s the avoidance of the noun. “The elephant in the room is created when people see a topic, problem or risk that impacts success, but they avoid acknowledging it, do not attempt resolution, or assume a resolution isn’t possible,” she writes.

There’s avoidephants, where you avoid conversations altogether, instead choosing to internalize your thoughts and feelings. There’s imagiphants, which are based on assumptions or beliefs without confirmation. There’s blamephants, where you blame someone’s action – or inaction – for a barrier. There’s nudgephants, which manifest themselves through passive language or dropping hints without addressing the issue directly. Then there’s deflectephants, where you change the subject or resort to jokes to avoid the conversation.

I talked with Noll Wilson about the book, why people avoid hard conversations in the first place and what we can do to effectively address elephants in the room.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Tell me about why you decided to write this book.

This is a topic I’ve been exploring and experimenting with for well over a decade. It felt ripe. It felt like I had learned enough and gathered enough practices where it was ready to be shared with a broader audience. Writing it during the pandemic reinforced how important it was for us to be able to have the conversations that we were avoiding. There’s a lot of really amazing books out there about how to have hard conversations or radical candor. One of the things that I heard a lot from people [through my job as an executive leadership coach] was, “We took this training but nobody’s changed behaviors.” So I got really interested in the avoidance side of it and how we can better understand that.

I noticed that you had a lot of Brene Brown quotes in the book. One is “Vulnerability sounds like truth and feels like courage. They’re not always comfortable but they’re never weakness.” I’ve got a quote of hers written on a sticky note on my desk that says, “You can choose comfort or you can choose courage. You can’t have both,” that came to mind when I read your book because you wrote about how asking questions and exploring the unknown does require courage. Why do we avoid difficult conversations?

We avoid for a lot of different reasons. Maybe it’s that we work in an environment or we’re in a relationship where it isn’t safe to challenge authority, disagree or speak up. Maybe it doesn’t feel safe because of lived experiences heading into a conversation. Sometimes we avoid because it’s more comfortable. We avoid because of past trauma. We avoid because we’re protecting our power. We also tend to overestimate negative responses from people.

If I were to have a new edition, that Brene Brown quote I included that you mentioned would perhaps be swapped out for one by Minda Harts, who wrote a book called “Right Within: How to Heal From Racial Trauma in the Workplace.” In a session that I got to attend with her, she said, “Nobody will benefit from your caution, but so many can benefit from your courage.”

The thing I will say, though, is sometimes what I’ve seen is that people will sometimes swing too far, like, “Oh, we just need to call it out.” There might be times where that’s actually not appropriate. There might be times where I choose to consciously not engage, because it might not be safe. Maybe I’m just not in the headspace or maybe I’m just choosing my battles.

Some people hold intersecting identities where the stakes may be higher for them to initiate those uncomfortable conversations. Could you talk about the power dynamics that may be at play?

If you’re an only female, if you’re an only person of color, if you’re an only LGBTQ person, there can be a situation where the risk is higher for you to speak up. You might be challenging something that is an accepted norm across the group. Whether we admit it or not, research shows that when women are more assertive and speak more directly, we’re perceived as people who aren’t as open to ideas. And then when you add on the intersectionality of a Black woman, for example, we know there’s the stereotype of an angry Black woman. It also depends on the situation. Is what we’re avoiding something to do with a process or does it have to do with something cultural about how we’re treating people? Does it have to do with my sense of safety? There’s those informal power dynamics that are very real and very much at play. And then there’s the formal power dynamics of “You’re the boss and I’m the team member, and the consequences of me speaking up are very different.”

When people are reflecting on their own work culture, they go, “We can have difficult conversations,” or “We can disagree.” Well, who actually is allowed to? Who feels safe to speak up and disagree? For me the question is not “Do we make it safe or don’t we,” it’s “What ways are we unsafe? Do we create a culture that’s unsafe for someone who doesn’t look like, sound like, and have our lived experience to speak up and to be able to speak out?”

When we think about either a second edition to the book or even a whole different book, that’s something I want to dig into more. I realized that while writing it, I was writing it through a process of a bunch of exploration for myself in that area, and I wasn’t ready to share those stories, because I didn’t feel like I could honor it well enough.

You introduce the concept of “Iowa nice” in the book. A lot of times people think Iowa nice looks like pulling over to help people on the side of the road, but there are more and more arguments coming out saying Iowa nice is really just this atmosphere where people avoid conflicts and avoid having those difficult conversations because they want to maintain that sense of politeness. How can we as Iowans overcome that conflict avoidance both in our personal lives and at work?

There’s nothing wrong with taking care of your fellow person. Like you said, we’re not talking about not pulling over. But there’s a real consistent unspoken value of wanting to fit in, there’s a real consistent value of sameness and keeping that peace and maintaining harmony. I once referenced the phrase “violent politeness” on Twitter and someone said they call it “weaponized civility.” If I say something to your face that actually isn’t accurate about how I feel about the situation, I’m lying. I’m not being truthful or authentic to myself or you.

I have to give credit to one of my colleagues, Gilmara Vila Nova-Mitchell, on this, but one of the things that we can do is normalize disagreeing respectfully. Not saying, “I think your idea is stupid,” but practice the act of saying, “Well, actually I disagree with that,” or “I have a different perspective,” or “I don’t see myself in that example.” Another way is to invite different perspectives and invite disagreements. “What am I not seeing that could get in the way? What are we not thinking about that could cause an issue?”

I have a client whose boss has a practice in one-on-ones who asks, “What’s going unsaid?” There’s something I really love about that. We have to practice being open and listening. When we aren’t used to having conversations of real feedback and conversations of disagreement, it can feel emotionally hotter than it needs to because we haven’t built up that muscle of “They’re just disagreeing with the idea. They’re not negating me as a person.”

The other thing I’m going to add particularly for Midwest women – and this is based on my experience – is we have essentially been conditioned to always nurture or take care of others and sacrifice ourselves. To be a martyr. To eat last. A really powerful thing we can do is to just ask, “What do I need in a relationship?” I can’t tell you how many times when we’re working with a group and we talk about that idea that when there’s issues in relationships, it’s because there’s usually a need that’s not being met and how many women go, “I don’t even know what I need.” So I think that there’s an act of courage in reflecting on what I actually need in this relationship and am I getting what I need and reminding myself that I deserve to ask for that.

You mentioned earlier about how you caution against barreling full speed ahead, and just throwing things out there. And instead you encourage people to get curious about themselves and each other first. What are some questions or prompts that people can ask themselves in order to practice self-awareness?

There’s still things I don’t know about myself. My husband and I’ve been together 20 years and there’s things I don’t know about him. When we can just remind ourselves, “What don’t I know in this situation, and how can I explore it more?” I spent years in management and then years supporting employee relation issues. One of the patterns that I noticed is that people would become emotionally frustrated or triggered, but they rarely took the time to get clarity around why. We owe it to ourselves to get that clarity so we can see the situation differently and then hopefully have a different kind of conversation.

Going back to specific questions you can ask yourself: “What do I absolutely know to be true in this situation, and what do I need to confirm?” “What values of mine are being stepped on or not being honored?” Or “What needs do I have that’s not being met?” Even just simply saying, “How do I feel right now?” is a really powerful way to check in. Self-awareness is not just experiencing something, it’s taking a step back and getting on the balcony and then observing it.

You gave an example in the book about how if someone is very direct in an email to you and doesn’t include pleasantries, you might think, “Oh my gosh, she’s angry with me,” when really she may just be being efficient. Then the value of yours that she’s stepping on is that you prefer quick chats or saying, “How are you doing?” or “Hope you had a great weekend.”

Yeah. Then you get curious about the other person. Ask yourself, “What value are they honoring right now?” I might not share the value, but that’s the thing with relationships. Most issues and relationships are perpetual conflict, right? It’s just a difference of values, a difference of opinions, a difference of lived experiences. One of the things I hear quite often is “This is just who I am.” I’m not going to ask you to not value that. You aren’t going to be able to adopt a value that you don’t share, but can we increase your range? Think of it like a singer. Really good singers have big ranges and they can sing a lot of different songs because they’ve built up our capacity to be able to sing more notes. For me it’s “How do we learn to sing more notes in our relationships?” How do we do this in a way that serves both of us?

You started writing this book before the pandemic and finished it up in the midst of it. Many businesses and organizations, including yours, continue to operate through hybrid or remote-only models. How can co-workers and teams effectively communicate and build those partnerships while not being in the same room?

We have to understand that when we move to hybrid or remote-only environments, one of the traps that teams fall into is that their communication becomes largely transactional. We lose those moments of transformation, like finding commonalities, connecting, or just having the space and time to explore projects more deeply. We might not have the situation where we just got out of a tense meeting and now we can walk to our desk together and talk about it. We have to just be so much more intentional about that and pay attention to our intuition of “Did that meeting feel weird?” and then getting curious about it like “Hey, did that feel strange to you? What are you feeling?” We have to be so much more intentional, which I don’t think is a bad thing.

The other thing I will say is that what we’ve seen in some teams is that with things that used to maybe become elephants, now I literally can shut off my camera and go to my safe space and not have the constant reinforcement of that [bad] meeting that just happened because everyone’s talking about it. So for some people, the virtual world has become a much safer place. But the risk is that we’ve become so focused on the task without taking the time to talk about the togetherness.

Without naming specific companies or businesses, what does it look like when a company does this really well? You talked about psychologically safe environments in your book. What does that look like?

In earnest, I don’t see it that often. I see it in relationships in a company, I see it in some teams, but I rarely see it on a larger scale, because humans are so complex. Sometimes we might be working with a team where they don’t have the psychological safety overall, but two people have built a really high level of trust, but it doesn’t extend to the whole team.

[A psychologically safe environment looks like one] where people can talk about hard topics, where there will be space held for disagreement, where people get curious. I would say that the teams that have the highest level of psychological safety verbally acknowledge each other a lot. It might be “Hey, Emily, I can tell that that was really hard for you to share, and I just want to thank you for sharing that with us.” There’s an awareness and people are tuned into where each other’s comfort levels are. Even team members telling the manager, “Hey, we think you’re beating yourself up too hard with this.” An ability to really consider and take ownership of potential harm that you’ve caused, or ways that you just didn’t show up at your best is another example.

I think so many people haven’t experienced a psychologically safe work environment, so they don’t even know what’s possible. There’s a level of toxicity that I think many people have tolerated because that’s just what you had to do. You didn’t realize it was a really unhealthy environment until you got out of there.

What should teams or leaders be striving for?

They should be striving for a culture where people belong. It’s not just inclusion, it’s belonging. Am I valued? Am I seen? Am I heard? What are we doing that’s getting in the way of what we intend to do? Part of that is a culture of courageous curiosity. It’s encouraging disagreements and really working on “How do we respond to feedback?” Relationships aren’t healed in the land of good intentions. One practice that I would love to see more of in teams and people in positions of power and authority think about is that courageous audit. What are we doing or not doing that’s actually getting in the way? When people are able to do that deep reflective work, that is much more powerful to make movement than us giving you any kind of to-do’s or how-do’s.

Writing with a focus for those who struggle to focus

Within author communities, there can sometimes be pressure to write books as if you’re an academic – saturating the pages with research and large vocabularies.

When Sarah Noll Wilson sat down to write “Don’t Feed the Elephants,” she said she struggled with the pressure to write it like that. After talking with a friend who said, “You should write the book that you want to read,” she thought about her own reading habits and her diagnosis of ADHD.

“I realized that I literally never finished books,” she said, acknowledging she often only gets through the first few chapters. “It’s not because they’re not great, but because with a neurodivergent brain, it can be hard to hold focus.”

She worked with her publicist to intentionally design the book for neurodivergent brains, using casual conversation in writing, text breaks, headers, illustrations and different font styles.

“When we can take care of people who might struggle, it will make it that much easier for the neurotypical brains,” Noll Wilson said.

She gave an example of a woman whose 12-year-old autistic son saw the book, picked it up and didn’t set it down for an hour. Every night for dinner, she said, he read it. Beyond that, he said, “Mom, I want to talk about the elephant in the room. I want to talk about how you respond to Dad when he’s trying to help because I think you have a need that’s not being met.”