Story by Emily Blobaum, graphics by Lauren Burt

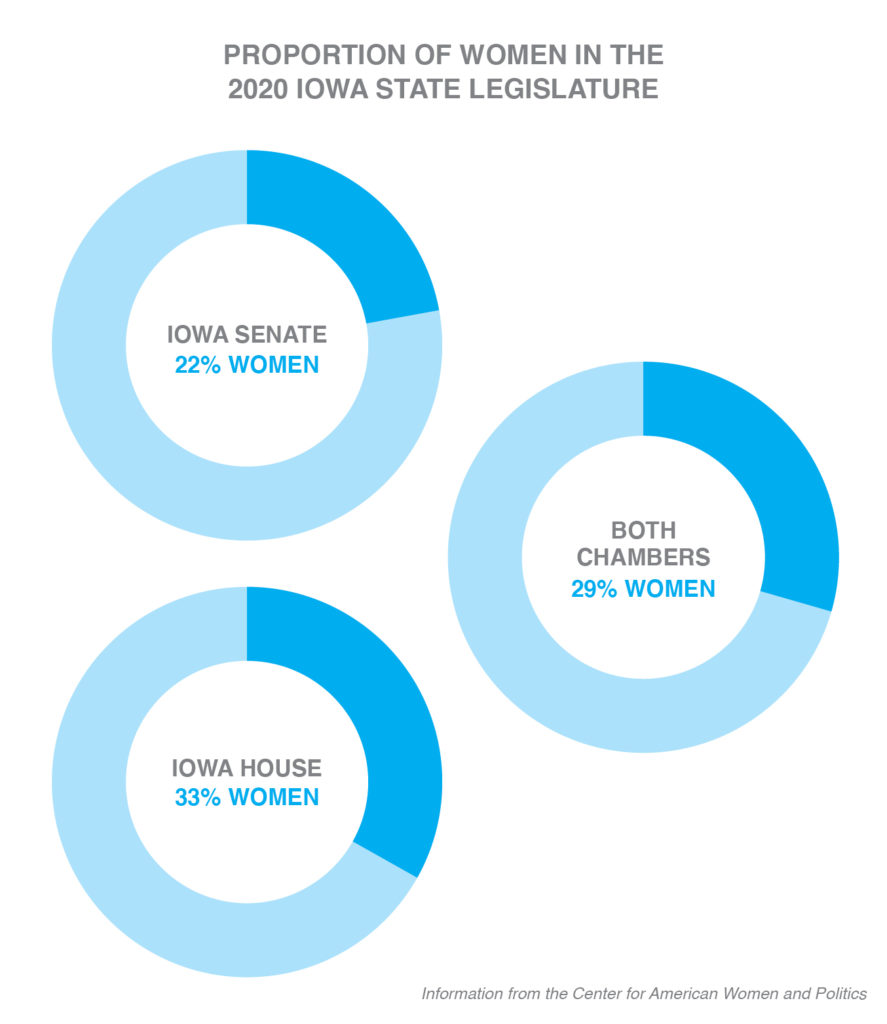

It’s no secret that women’s representation in political office is unequal. Women make up more than 50% of the population in Iowa, but make up only 29% of the state Legislature. Nationally, women make up 23.6% of the 116th U.S. Congress.

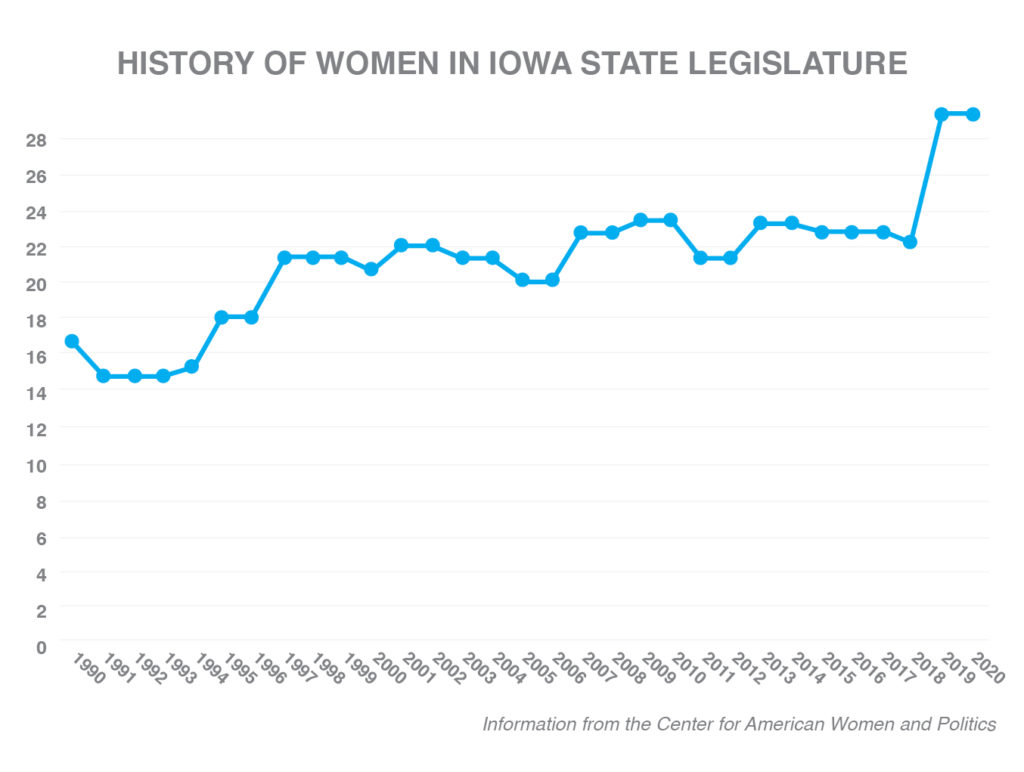

The percentage of female candidates in Iowa’s general elections has seen increases every year since 2010. In the 2018 general election, 32% of the candidates were women. Nearly half of the 83 women who ran for Iowa’s state Legislature were elected.

Having women represented in politics is important for both symbolic and substantive reasons, said Karen Kedrowski, director of the Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics.

Political scientists refer to the former as descriptive representation. This looks at the identity of elected officials reflecting the demographics of the people they work for in terms of race, gender, ethnicity, age, religion, etc.

“We know that when young children see someone who looks like them in positions of power, it opens up in their minds the possibility that they could achieve similar positions of power,” Kedrowski said.

The latter is focused on policy.

“When you have more diversity of people in public life, the agenda expands,” Kedrowski explained. “New issues are brought to the fore. People think about issues in different ways. … Diversity benefits people both in terms of substantive input and in terms of legitimacy of government.”

A closer look

Let’s start from the top and work our way down.

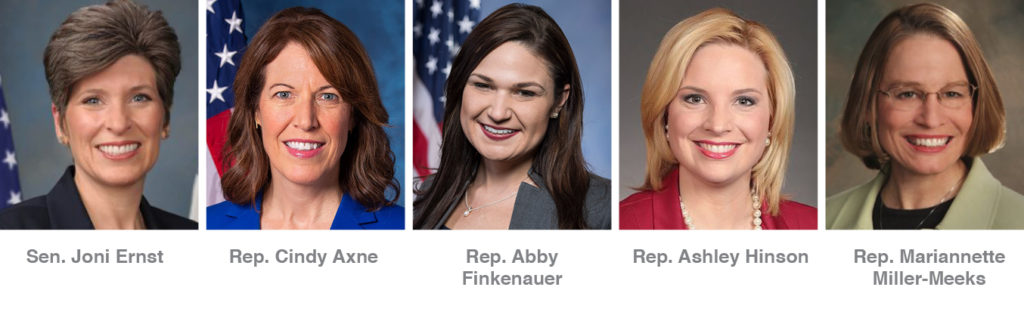

At the national level, five women have represented or will represent Iowa in the U.S. Congress.

Elected in 2014, Sen. Joni Ernst was the first woman to represent Iowa in the U.S. Senate.

In the 2018 election, Reps. Cindy Axne and Abby Finkenauer became the first women to represent the state in the U.S. House. Reps. Ashley Hinson, who defeated Finkenauer, and Mariannette Miller-Meeks, who narrowly defeated Rita Hart, were elected this year.

“The progress Iowa has made in women’s representation in federal office is significant,” said Kelly Winfrey, coordinator of research and outreach at the Catt Center, in November. “Just six years ago Joni Ernst became the first woman Iowans sent to D.C., and now four of six will be women. That’s progress.”

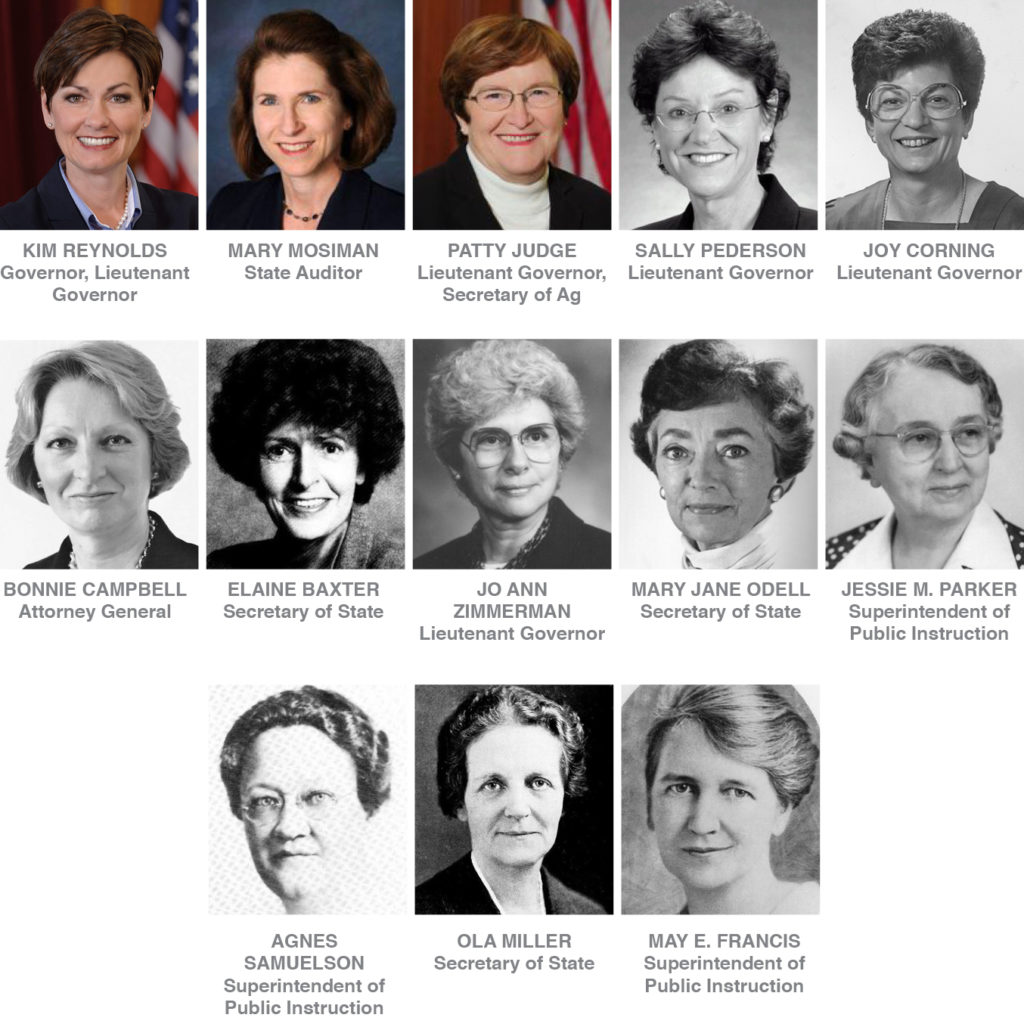

Thirteen different women have held six statewide elective executive positions, including governor, lieutenant governor, state auditor, secretary of agriculture, attorney general and secretary of public instruction, now known as director of the department of education.

The Iowa Legislature currently has 44 women in the House and Senate, amounting to 29%. This is slightly better than the national average, which is about 28%, said Kedrowski.

But is 29% acceptable? Kedrowski said she would like to see Iowa move up in the rankings of women in the state legislature. Right now, Iowa ranks 25th.

“[Twenty-nine percent is] enough to be able to influence the agenda,” Kedrowski said. “But having said that … I would be happy if we could see that women were as represented amongst our elected officials as they are in the adult population. … Women are 52% of the voting-age population, so I think it would be great if we approached 52% amongst our elected officials.”

The Catt Center reports that the Iowa Legislature will be down at least one woman when the Legislature convenes Jan. 11. The Iowa Senate will gain two women, but could lose one depending on what happens with Miller-Meeks’ seat. The Iowa House will be down three women.

When it comes to representation of women of color in public office in Iowa, numbers are extremely low. Currently, only two Black women serve in the state Legislature, both in the Iowa House: Rep. Ruth Ann Gaines and Rep. Phyllis Thede. Nationwide, women of color constitute 7.5% of the total 7,383 state legislators. That rate is better at the national level where 38.1% of the 126 women serving in the 116th U.S. Congress are women of color.

So, what’s the deal?

Kedrowski says there a few reasons why we haven’t reached gender parity in political representation:

- Imposter syndrome. “Women don’t think that they’re capable. One of the best quotes I’ve seen is in a textbook and says, ‘A woman thinks that she needs a Ph.D. in economics to look at a budget, whereas any guy who sells used cars thinks he can do it.’ And that’s really true. … We find that even highly credentialed women who have lots of formal education think that they just don’t know enough to be able to run. And that sort of thing rarely, if ever, comes out of the mouth of a man.”

- Caregiving responsibilities are at play, both with young children and aging parents. “Women’s caregiving responsibilities are much heavier than those of men. … The care work is unrelenting and unrecognized and it’s also not something that can be used as a campaign expense.”

- Women don’t see themselves as candidates for office until they are motivated by an issue. “You will hear a woman candidate say over and over again, ‘I never thought I would run for [blank]. But then something happened and I got mad and I decided that I needed to do something about it.’”

- Job flexibility. “There’s a good reason why lawmakers are usually lawyers. Because that’s a kind of job that you can do half the year. Women are not necessarily in jobs that offer that kind of flexibility.”

What we can do about it

Kedrowski implores political party leaders to be intentional about recruiting women and women of color.

Secondly, she recommends that women — and anyone, for that matter — who are interested in running for office attend campaign training workshops, like Ready to Run, a nonpartisan training program that encourages women to run for elective office, position themselves for appointive office, work on a campaign or become involved in public life as leaders in their communities.

“These kinds of campaign training schools really try to demystify the process of running for office but also encourage women to think about what they bring to the table and what they know,” Kedrowski said.

Lastly, she doesn’t want women to count out running for a local board or commission.

“A lot of local governments are just crying for applicants. They’ll have vacancies and have few to no applicants at all. And they do important work and make important decisions. … It’s also something that’s easier to fit in with schedules. It could be meeting once a week or once a month, at night.”