Communities, hospitals and doctors seek solutions amid Iowa’s changing maternal health and economic landscapes that drove the loss of 40 birthing units since 2000.

By Sarah Bogaards, staff writer

Editor’s note: This is the first story in a three-part series focusing on the closure of birthing units in Iowa, the factors driving the trend and how it is changing maternal health care in Iowa. Part one looks at the overall problem, part two explores a couple of communities that have lost a birthing unit in the past two decades, and part three looks at potential solutions.

Angie Pietig had positive experiences delivering her two daughters at the UnityPoint Health-Marshalltown birthing unit in 2009 and 2014. Both were born in the hospital with no complications, and she would have delivered her son there as well if not for a high-risk condition she developed.

Learning the unit would close in 2019 made Pietig sad, less for herself as she was not having more children, but more for the community.

A teacher at Franklin Elementary, which is located just down the street from the hospital, she said the closure takes away the convenience of having services available locally. When she was pregnant with all three of her children, she would always schedule her prenatal appointments right after school or over the lunch hours.

The community connection created by the unit would be missed as well, Pietig said. She recalls attending first-time parenting classes offered by the hospital every Monday night with her husband and newborn daughter, and receiving a gift from a nurse the night her second daughter was born.

With the unit gone, Pietig said she was unsure how her friends would adapt.

“I felt concerned for some of my friends … who are still adding to their families and where they’re going to have to go for care,” she said.

One of those friends is Dani Minkel. She also works at Franklin, but as a school counselor, and is expecting her third child in December.

Minkel’s experiences mirror Pietig’s — the deliveries of her two daughters in 2014 and 2018 at the hospital both went smoothly. But her next delivery will be in the Des Moines metro area.

She was frustrated by the closure in Marshalltown as she contemplated driving two hours round-trip for a 10-minute prenatal checkup and the potential need for emergent care with only the hospital’s ER available to help locally.

She said the news made her think: “How can a town of 30,000 people go without this medical service?”

Fortunately, Minkel has been able to see midwives who travel from Des Moines at a clinic in Marshalltown for her prenatal care, but she knows other expecting parents who are traveling to Ames or Des Moines, and some who did so even before the unit closed.

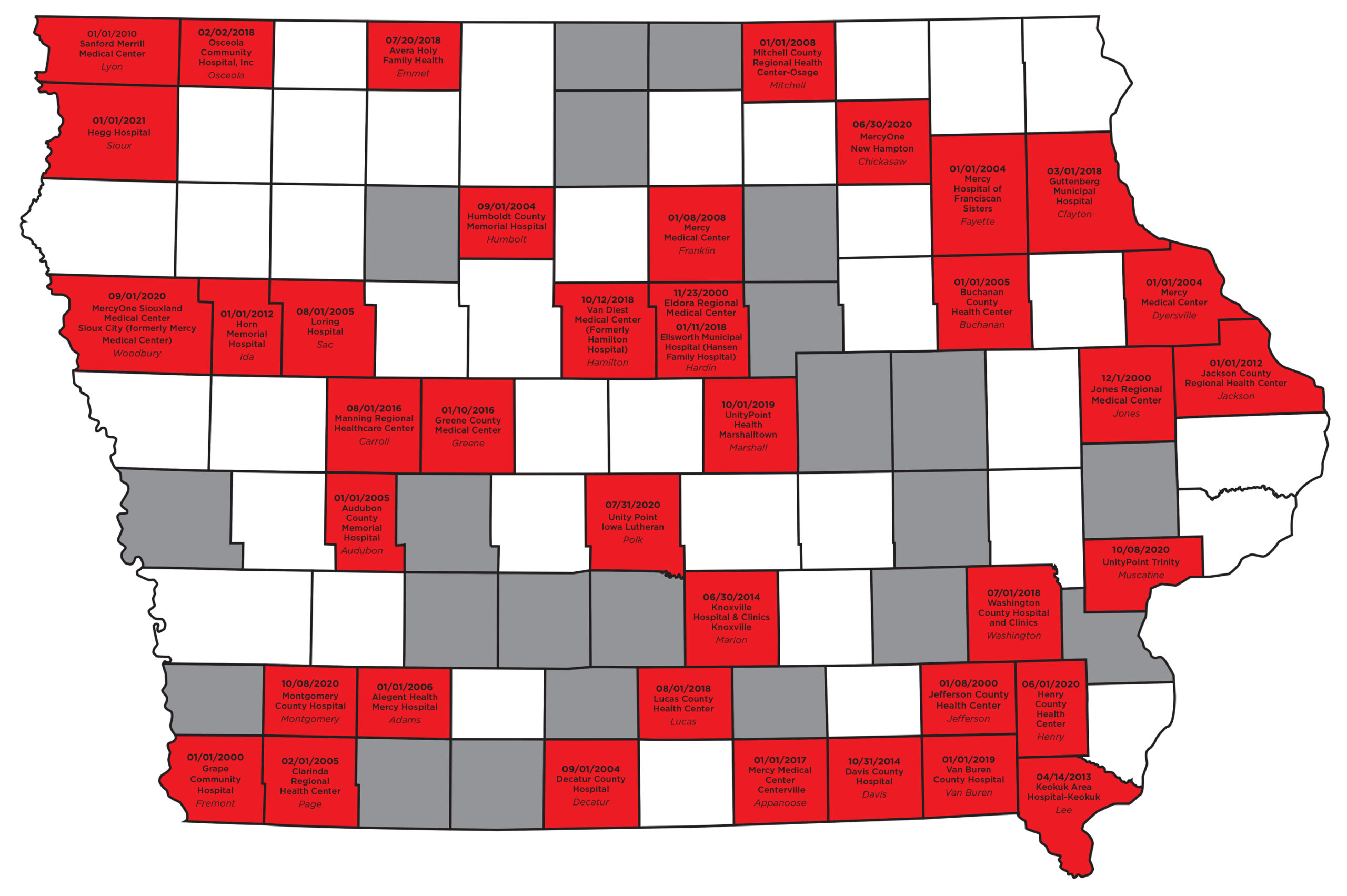

Marshalltown is not the only community navigating this experience and transition. Its hospital is just one of 40 in Iowa to close a birthing unit over the last 20 years. Without other options, parents are adapting while maternal health care in Iowa is undergoing a significant transformation.

In 2000, 77 of 99 Iowa counties had at least one birthing center available. By 2010 closures had reduced that number to 62, and as of April 2021, only 46 counties in the state had at least one open birthing center.

That’s 20 years of loss across communities that are primarily rural.

Graphic by Patrick Herteen

The anatomy of a birthing unit closure

The reasons behind each closure are different, but from working with hospitals across Iowa as co-director of the Statewide Perinatal Care Program, Dr. Stephen Hunter said he finds common themes.

No. 1 is low volume. Often, hospitals are not delivering enough babies to support the existence of a birthing unit.

“I like to joke in some of the presentations that I give that when I was a kid growing up in Utah, I used to ride horses and motorcycles,” Hunter said. “[The motorcycle] I had to feed only when I was riding it, [the horse] I had to feed whether I was riding it or not,” Hunter said.

“A labor and delivery unit is like a horse.”

Paying doctors, anesthesiologists, nurses and support staff to be on call 24/7 for births that aren’t happening becomes financially infeasible for hospitals, particularly ones that serve less populated areas.

Even if a hospital has the funding to support hiring, the question remains if they can find doctors to work in obstetrics. Hunter, who is also vice chair of obstetrics at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, said Iowa ranks last in the U.S. in OB-GYNs per capita. There were 280 OB-GYNs in Iowa in 2018 to serve the state’s roughly 600,000 women of reproductive age, who are defined as women ages 15 to 44.

The natural question, then, is: Why aren’t there enough births or OB-GYNs?

But the answers are multifaceted and lie beyond the hospitals, rooted in evolving trends like the state’s population and workforce changes.

Liesl Eathington, coordinator of the Iowa Community Indicators Program at Iowa State University, said the 2020 census data stood out to her because it showed that the overall pattern of Iowa’s population changes in the last 10 years looked almost identical to those from 2000 to 2010.

Iowa’s population has grown about 4% in each of the last two decades, and according to the USDA’s Economic Research Service, each decade saw rural Iowa lose about 2% and urban areas gain 9.9%.

Eathington said these patterns and similar population trends in other Midwest states are confirmations of the ongoing urbanization in Iowa, especially since 2000.

Urbanization happens in many industries, and in health care she said it is taking the form of more regional hospitals as fewer independent ones can deliver obstetric services at a “small scale” and meet new demands for technology.

“In some sense the things that are driving these trends are resulting in outcomes that are better on average for consumers to have more choice, maybe higher quality services, more technology, but it does create the burden on the people out in those more remote areas that they have to travel farther to get these things,” she said. “On average, maybe consumers are better off, but we definitely have inequity in terms of who’s more able to take advantage of that.”

Eathington said these changes are the result of the urbanization of population and services that has been happening in Iowa for the last 20 years. Other Midwestern states with similar demographics are seeing the same changes, she said.

Adding to the problem is that Iowa relies on family medicine physicians to fill the gaps created by the lack of OB-GYNs in Iowa.

Those practicing family medicine in Iowa often assist with natural deliveries, but usually depend on general surgeons to handle cesarean section deliveries.

Offering prenatal care and deliveries as part of a family medicine practice does not require extra certifications, but interest has declined, as becoming the only physician to offer those services, especially in small hospitals, is not typically desirable for new doctors.

In 1988, around 68% of family physicians in Iowa were willing to or planned to practice obstetrics upon completion of their residency. That figure dropped to 18% by 2018.

Building awareness, support for maternal health

Hunter is helping lead research to address maternal health issues like birthing unit closures and Iowa’s maternal morbidity rate, which have gained statewide attention but not until more recently.

When visits to birthing units for the Statewide Perinatal Care Program were being canceled due to closures, Hunter decided to survey hospital CEOs to understand why.

Just two days before the first COVID-19 cases were confirmed in Iowa, the results were discussed at a conference held by the University of Iowa Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

The event brought together hospital CEOs and staff, state legislators, and representatives from the governor’s office, kick-starting awareness and efforts to address a different public health crisis in the state, Hunter said.

Hunter is now the principal investigator on a $10 million grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration seeking solutions in the space, but he said Iowa needs cohesive statewide interventions, and the grant is only the beginning.

“We didn’t get here overnight. We’re not going to fix it overnight,” he said.

1 Comment

Micholyn Fajen · December 8, 2021 at 7:30 pm

Interesting trends in rural areas.

Comments are closed.