By Emily Kestel, Fearless editor

Editor’s note: This is the first installment of a two-part series that looks at issues with child care in Iowa, which experts believe to be a big factor affecting local and national economies. Part one introduces the current workforce shortage in the industry and what’s currently being done to address the lack of available slots in the state. Part two will detail the recommendations from the Child Care Task Force, which was established by Gov. Kim Reynolds in 2021 to address the child care crisis.

Friday the 13th has long been considered a day of bad luck. It certainly was a bad day for Miranda Niemi this August.

Niemi runs Collins Aerospace Day Academy in Cedar Rapids, which is the largest child care center in the state.

That day — Aug. 13 — was the last day for six of Niemi’s employees, which meant that it would be the last day that she would spend her entire workday sitting at the executive director desk.

To keep in line with the strict DHS staff-to-children ratio requirements, Niemi had to teach 13 of the center’s 3-year-olds full time in addition to maintaining her responsibilities as executive director.

“[Aug. 13] was when we nose-dived,” she said. “I thought COVID was going to be the worst thing I’ve ever had to deal with as a director.

“I think the [workforce] crisis might be.”

The Day Academy is licensed for 448 kids with a desired capacity of 380. Currently, there are 278 kids enrolled, and there are about 120 kids on its waitlist, Niemi said. On a good day, there are between 65 and 70 staff members working, but right now, she’s running in the high 50s, which means she can’t add any more kids until she can hire more staff.

Niemi said that since August, she’s lost between 12 and 15 staff members. All but one have left the industry completely, opting to work in the medical field, become office managers or stay at home with their young children.

Starting wages at Day Academy are between $11.41 and $13.03 an hour, depending on education and experience.

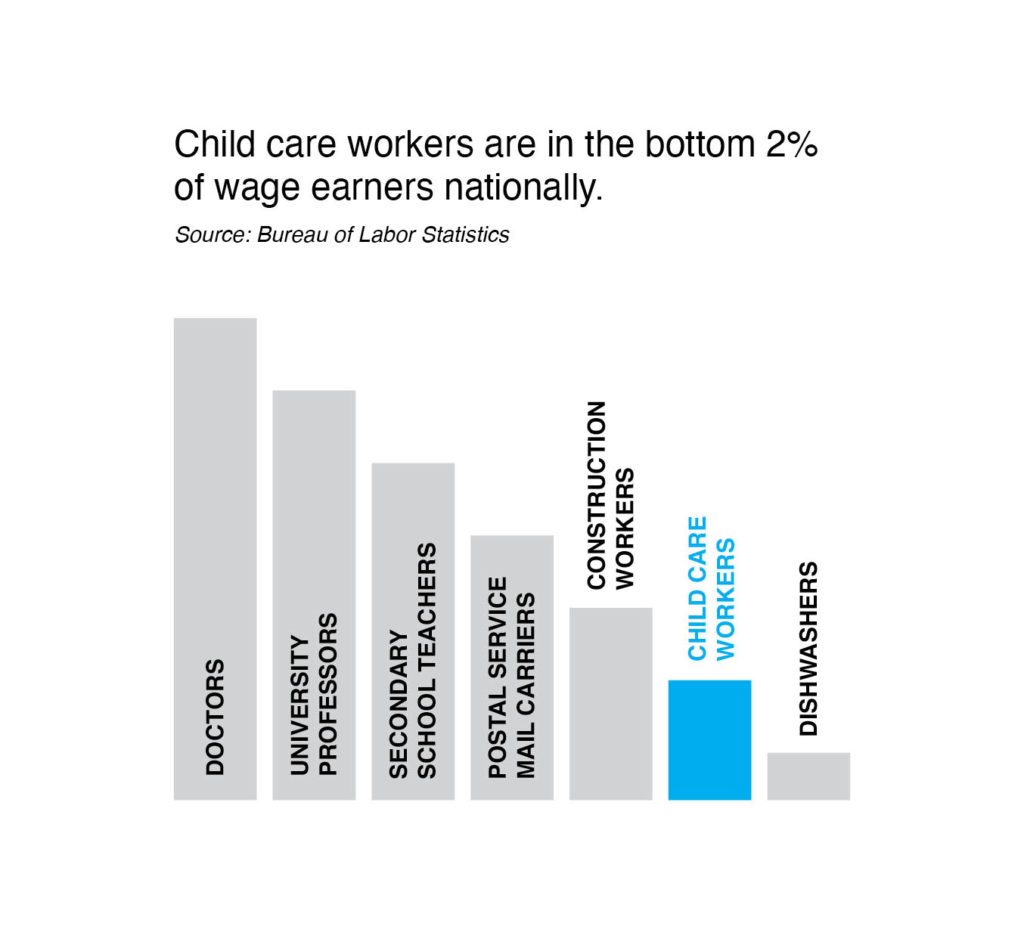

Child care workers in Iowa make an average of $10.18 per hour, or $21,170 per year — the lowest among surrounding Midwest states and lower than the national median pay of $25,460 per year. Most programs can’t afford to pay benefits, either.

“They left because of the wages,” Niemi said. “They’re crying in my office because they don’t want to leave because they like working here. … But they needed to find something that could actually pay their bills.”

Child care providers across the state and country are facing similar situations.

Dianna Williams, director of the Ann Wickman Child Development Center in Atlantic, noted that some of her staffers have second jobs working in the school system or at a nursing home.

“Child care providers are not paid near enough,” Williams said. “A 16-year-old can make two to three times that much money [without] having to do near the work that these ladies and men are having to do on a daily basis.”

Currently, the Wickman center has 39 people on staff to work with the 97 kids who are enrolled, though Williams still said she needs five or six more people. Starting wages for providers at the Wickman center are between $9.50 and $10 an hour.

“We’ve had to turn to a $500 hiring bonus within the last year to try and get people to come into the door,” Williams said.

Ann Wickman Child Development Center operates through the Nishna Valley Family YMCA in Atlantic. All of the employees at Wickman are therefore YMCA employees. “We’re lucky to have the YMCA that owns us because had we not, I’m not sure if we would have been able to survive COVID,” Dianna Williams, director of the Wickman center, said.

U.S. Labor Department data shows that the child care services industry nationwide is still down more than 100,000 workers compared with pre-pandemic levels. Because of the child care industry’s unique position in its effect on the rest of the economy, that’s a problem.

Without enough employees available, child care providers often have to turn away children in order to maintain the DHS ratio requirements.

When children are turned away, working parents are left scrambling to find other options for care. If they can’t find any — which isn’t uncommon, due to the severe shortage of slots — they may be forced to quit their jobs to stay at home.

That’s why Niemi believes that fixing the child care workforce issue is a key first step to getting the economy back up and running.

“If they don’t fix us, then there’s not going to be people available to go back to work because they’re not going to have child care.”

Parent perspectives

Kaitlin Emrich, a mom of two kids — Jack, 9, and Paige, 5 — in Vinton, found herself without child care for Jack at the beginning of the pandemic.

Both she and her husband were essential workers — she in public health, he in public works. Paige at that time was young enough that she was in full-time day care. Jack, however, needed someone to watch him after his elementary school closed in March.

Left without any other options, Emrich and her husband made the difficult decision to send Jack to live with a grandparent an hour away in Tiffin.

For 11 weeks, every Monday morning Emrich would meet her father-in-law halfway in Cedar Rapids to hand off Jack, and would then pick him up on Friday afternoon.

Emrich had trouble finding child care for Jack even pre-COVID. Two in-home providers closed and she was dismissed from two because Jack “had needs that care providers weren’t able to meet.”

She said the child care staffing crisis was the underpinning reason that they weren’t able to stay at the child care center, adding that the staff didn’t have the proper training to be able to navigate the situation with her son.

“There needs to be more of a support system for the whole child care sector,” Emrich said. “I really think that there needs to be more to assist in the value that providing stable, quality child care can provide for families.”

***

For six months after Haley Close’s first daughter was born, she had to pass her around to friends and family — “whoever could take her” — due to the lack of child care in Dysart, a town of 1,300 in Tama County.

She later snagged a spot at an in-home facility in Vinton — 30 miles out of the way from where she worked in Waterloo.

Less than a year later, Close and her husband ended up moving from Dysart to Vinton because the drive got to be too cumbersome.

“I can’t keep doing this. I can’t keep driving an extra 30 minutes, especially in the winter,” Close recalled thinking.

Moving to Vinton didn’t magically solve the child care issue once and for all, though.

“We’ve gone through a day care a year,” Close said, whose kids are now 2 and 6. “We’ve loved all of them, it’s just for whatever reason, they don’t work out. Providers leave for different opportunities, which I can’t blame them for.”

She said that moving small kids from provider to provider so often makes it hard for them to create a bond.

“You really want them to be going to a place that they feel like it’s their second home, where they feel comfortable and loved and cared for. Throwing that kind of wrench in their little lives is a much bigger deal than we really even know.”

‘It’s never been this bad before’

While providers and advocates all agree that child care has been an issue in the state for a long time, many describe the current situation as the worst it’s ever been.

“I can pretty categorically say that [child care] has been a problem for quite a while. Even before COVID … the hue and the cry was growing,” said Dave Arens, a founding partner at Private Wealth Asset Management and a board member of Early Childhood Iowa. “The economic supports, particularly for families in need, haven’t been growing to the level of costs for the providers.”

The child care crisis is especially problematic in Iowa, where the state is a leader when it comes to the percentage of families with all parents working outside the home. Pre-pandemic, that level was 75%, compared with a national average of 66%. That means child care for Iowans is especially necessary.

There’s no one reason the issue of child care became a crisis, but there are several key barriers at play.

There’s the issue of availability. Iowa is home to about 5,000 child care programs and 173,000 total spaces that are licensed with Iowa Child Care Resource & Referral. That may sound like a lot, until you consider that there are more than 235,000 children age 5 or younger in the state.

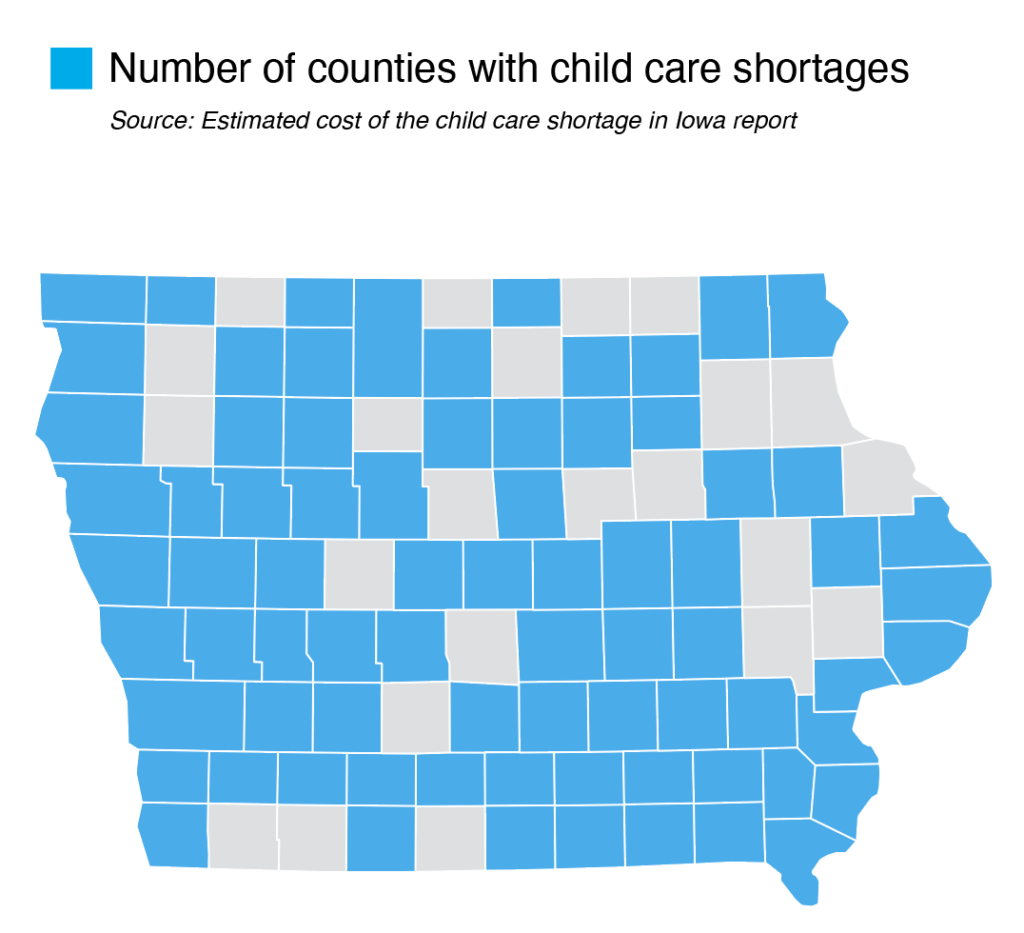

About a quarter of Iowa’s population lives in a child care desert, which is an area where the demand for child care far exceeds the availability of providers and open slots.

When the Wickman center first opened in 2010, Atlantic had 39 child care providers. Now there’s 18, Williams said. Kids at Wickman come from 14 towns and four counties. Some families have had to drive in from Manning, Audubon and Shenandoah — the last of which an hour away.

Some child care centers are known to have a wait list of more than 100 kids.

In the last 10 years, Iowa has seen a 56% drop in the number of child care programs and a 6% drop in the number of child care spaces.

Raven Walker, who is an in-home provider in Council Bluffs, said that in the entire 11 years that she’s been in business, she’s met just three providers who have retired from child care. The rest have either burned out or switched to a different career.

“It’s a physically and mentally exhausting job,” Walker said. “As my own kids approach school age … it’s going to be a constant battle for me if I choose to stay in this or not.”

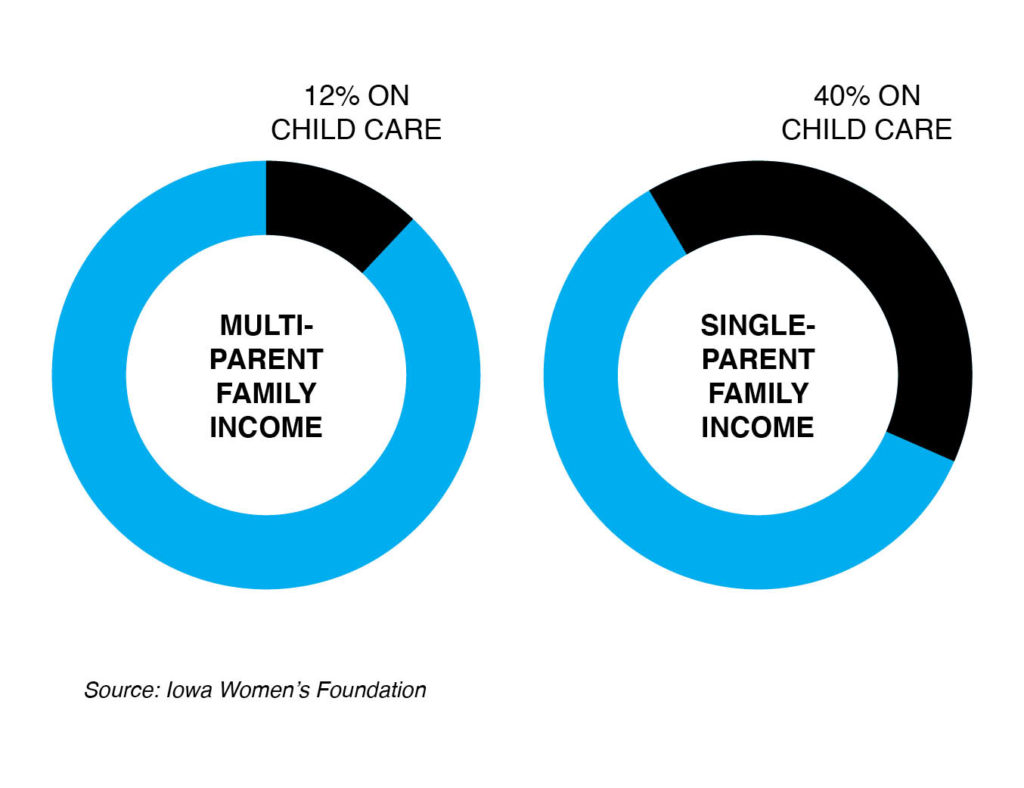

There’s the issue of affordability. An Iowa family earning a median household income spends an average of 12% of their income on center-based child care — higher than the national 7% affordability benchmark. For a single parent earning the median household income, that rate is more than 40%.

The average weekly costs for an infant in child care in Iowa — taking into account both in-home and center-based care — is between $119 and $218. Another estimate showed that the average monthly cost of child care in Iowa is $1,031.

Some rates are even as high as $500 a week, said Jennifer Banta, vice president of community engagement and advocacy at the Iowa City Area Business Partnership.

“I have one family with twin 3-year-olds,” Amy Bice, an in-home provider in Cherokee, said. “I handed them a receipt at the end of the year for $18,000 that they paid me.”

In the last 10 years, the weekly cost to send children to a provider has increased — by 22% to send an infant to an in-home provider and by 44% to send an infant to a licensed center.

State-funded financial assistance is available, but only for families whose income is at or below 145% of the federal poverty level — $38,425 for a family of four or $25,259 for a single parent with one child.

In Iowa, more than 18,000 children — or 10,000 families — currently receive child care assistance.

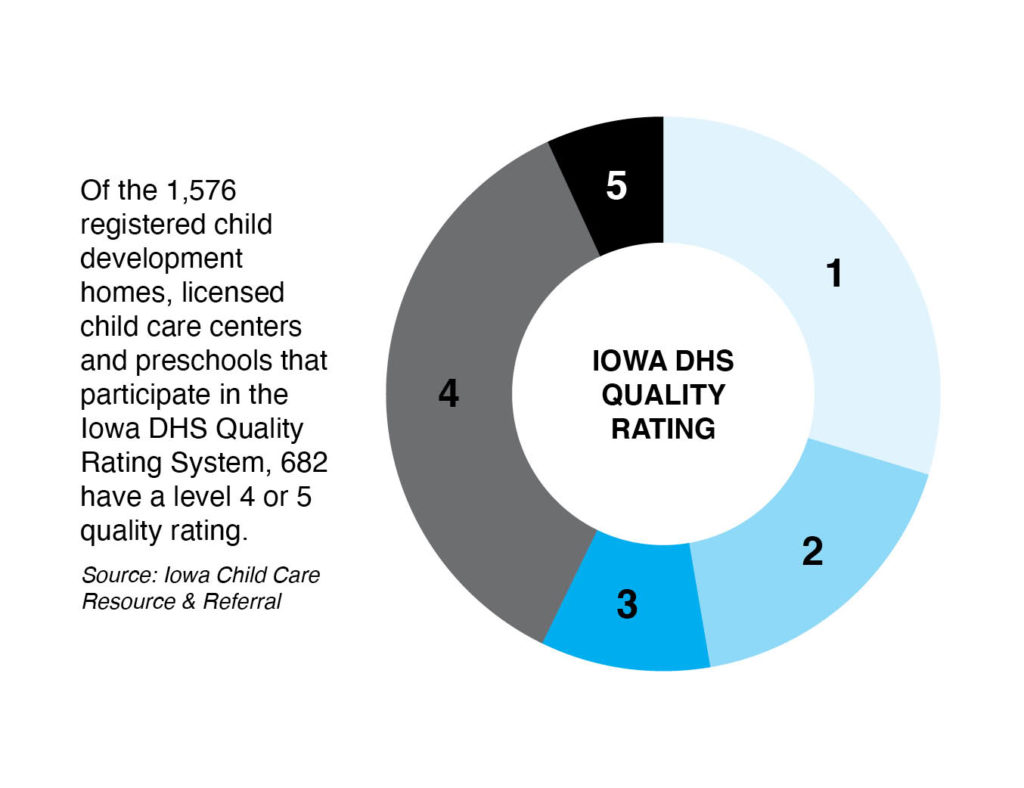

Then there’s the issue of quality. As of July 2021, of the 1,576 registered child development homes, licensed child care centers and preschools that participate in the Iowa DHS Quality Rating System, just 682 have a level 4 or 5 quality rating.

“You don’t just want a babysitter for your kids, you want your kids in a situation where they’re learning how to play with other kids,” said Janee Harvey, division administrator for Adult, Children and Family Services at Iowa DHS. “I’ve talked with a number of kindergarten teachers who said they could immediately tell which kids were in a regulated center or development home.”

Child care is not just bad for parents, though. Providers are also hurting.

Already operating on razor-thin margins, many providers were forced to close during the pandemic. While many of them were able to reopen, they continue to face an uphill battle in being able to stay afloat.

“I always like to say to a business, ‘Imagine if all of a sudden you lost all of your revenue and your expenses were going up and you couldn’t control them.’ That’s what our child care providers are dealing with right now. They’re in a worse financial peril than they’ve ever been in,” Dawn Oliver Wiand, president and CEO of the Iowa Women’s Foundation, said.

Erin Monaghan, director of Better Tomorrows, said several centers in Benton and Tama counties are in very fragile financial positions.

“I am incredibly worried that they are going to close before [the state’s stabilization grants] are released. … They’re probably looking at 10 months or less; … they need this money desperately,” Monaghan said. “Every time I talk with child care providers, I can hear how defeated and stressed and frustrated they are. It’s so disheartening, … knowing that this is such an important job.”

‘We’re hurting ourselves by not paying attention’

Iowa Child Care Resource & Referral is the state agency that focuses on quality child care by providing services and information to providers, parents and communities.

Joanne Lane, affectionately known by some as Iowa’s “child care godmother,” led the agency when it launched in 1992 up until her retirement in the early 2000s.

Documents she shared with the Business Record show that availability of regulated child care has been an issue since the beginning of tracking referrals and supply in 1980, and that it has always been considered an essential family support.

“Consider the cave woman who needed to go down to the river to wash clothes,” Lane wrote. “During those times and for many generations, child care arrangements tended to be informal, provided by extended family members or neighbors.”

After the Industrial Revolution and the need for women to join the workforce during the war, the need for child care grew.

“It’s not like the old days where you used to be able to find the lady down the street, and she could come and watch your kids,” Williams said. “Everybody’s working. … It takes both incomes in order to be able to survive, and they need some place that they can take their kids,” Williams said.

Iowa Child Care Resource & Referral worked for decades to increase business engagement on the issue and advocated at the municipal and state government levels, but progress was slow.

“CCR&R had been working on the issue for a long, long time and weren’t getting anywhere,” Oliver Wiand said. “Everything was being done in silos. People weren’t getting it.”

Arens, who has been involved with Early Childhood Iowa for more than 16 years, said that throughout his tenure on the board, he tried to persuade the Legislature to put a focus on the 0-5 population, but did not succeed.

“I have sat before previous governors, I’ve sat in the House and Senate chambers and talked about long-term investments for the benefit of our children because of the power and value of early childhood education. It resulted in exactly zero dollars’ difference to the state budget,” Arens said.

Conversations around child care were still happening, though they’ve never been as elevated as they are right now, said Mary Janssen, a regional director at Iowa Child Care Resource & Referral.

Sometime around 2017 or 2018, a coordinated rebranding effort elevated child care as an economic issue.

Seven years ago, Kyle Roed, then a human resources manager at MasterBrand Cabinets, discovered that the company was losing four to five people per month at its Waterloo facility due to lack of child care, which was ultimately costing the company $20,000 a month in turnover costs.

Roed got in touch with Janssen and asked what the solution was.

“I remember the conversation vividly,” Roed said. I asked, “‘Who’s doing something that has solved the problem?’ And the honest answer was, well, nobody, really.”

Around the same time, Iowa Child Care Resource & Referral joined forces with the Iowa Women’s Foundation, which had in recent years determined that child care was a key barrier to women’s economic self-sufficiency.

“It was really time to come together,” Oliver Wiand said. “And I think, honestly, it took reframing child care as an economic issue and a business issue and not the family issue to really start to get people to see it.”

Said Roed: “We used to go in and talk to businesses and I’d have to explain the problem statement — that there weren’t enough day care spots and it was too expensive — 16 different ways. Now I walk in and a few people are like, ‘Yeah, this is a terrible problem we need to fix.’ So I think there’s good momentum.”

If it wasn’t apparent then, it’s crystal clear now. As of September, nearly 1.6 million moms of children under 17 were still missing from the labor force, many of whom were forced to drop out to care for their children.

“Businesses are looking around, saying, ‘Where did my help go?’ ” Arens said. “My help is home taking care of their child because there was no care available.”

If nothing else, child care advocates say, the pandemic heightened the need for child care.

It needed to be significant enough and made enough fuss about in order for people to start taking a look, Angela Lensch, an early childhood educator and board member of Early Childhood Iowa, said. “We’re really hurting ourselves by not paying attention to the issue.”

If you build it, will they come?

In 2017, the Iowa Women’s Foundation launched the Building Community Child Care Solutions collaborative.

The nonprofit went to 18 communities across the state to meet with stakeholders about potential solutions to increase the availability of quality, affordable child care. Solutions included building or expanding child care centers, encouraging businesses to add child care benefits, and working with community colleges to educate the future child care workforce.

The collaborative is now operational in 44 communities, including the 1,151-person town of Glidden in Carroll County.

The town is surviving mostly on in-home day care, Lensch said.

When those limited number of slots fill up, that poses a problem to parents, who then have to go out of town to find child care, some as far as Jefferson, which is 20 miles away.

That creates a rippling effect, Lensch explained. Parents are taking their finances out of town; some will keep those kids in that town’s school district for stability, which could then lead to the parents moving to that town to make it more convenient.

According to the latest data on child care deserts from Iowa Child Care Resource & Referral, 40% of Iowa towns have children but no known child care. Five percent, or 55 towns in the state, have no children at all.

Glidden has seen declines in population every year since 2012.

“We have to … keep the students close,” Lensch said.

About three years ago, community members in Glidden began conversations about the need for a child care center. With help from the Iowa Women’s Foundation, community stakeholders talked about what was needed and how they would make the center a reality.

Lensch pushed hard for community members and businesses to get involved financially, frequently citing the 13% return on investment figure.

They started fundraising in September 2020, raising $1.4 million in six months. They received many private donations as well as $175,000 from the Child Care Challenge Fund and $500,000 in community development block grant funds from the Iowa Economic Development Authority.

Projected to open in fall 2022, the Lil’ Wildcat Education Center will have capacity for 56 to 60 children.

Lensch said she isn’t concerned about whether there will be enough kids to fill the center, but rather whether there will be enough people to staff it — as if it were a questionable “Field of Dreams” situation: If you build it, will they come?

“We have parents clamoring when they can get on the list,” Lensch said. “The staffing is the biggest thing. … People don’t want to come into the position. … That could be an issue, a big issue.”

Two-and-a-half hours away in Benton County — where four of the seven census tracts are designated as child care deserts — Monaghan shared identical concerns.

“If we build something new, will they be able to attract employees? Unless child care providers are paid a livable wage and receive benefits … we may end up with an empty building.”

‘There has to be a light at the end of this tunnel’

At the height of the pandemic, 60% of providers closed their doors, at least temporarily, Harvey said, adding that she’s proud of the work DHS did to help them reopen.

Using CARES Act funding, DHS gave out monthly stipends ranging from $500 to $2,000 to providers to help them stay open and began covering unlimited absent days.

“We’re proud of the work we did when COVID started to hit,” Harvey said. “Iowa moved aggressively. We received tons of emails from people saying that ‘without this financial support, we would have closed.’”

Erika Fuentes, director of Child Development Programs at the Crittenton Center in Sioux City, praised the monthly stipends that were doled out.

“Let me say this. DHS, they get a bad rap, but my Lord, they worked hard to make sure they were helping us and putting things into place to help child care places stay open,” Fuentes said.

The Iowa Legislature also worked on several policy measures that focused on early childhood.

Three child care bills passed in 2021: H.F. 302 addressed the child care cliff effect, H.F. 260 allowed unregulated in-home child care providers to care for up to six children instead of five, and S.F. 619 raised the upper income limit for those eligible for child care tax credits to $90,000, up from $45,000. Three other child care bills passed through the Iowa House, but not the Senate.

Additionally, Gov. Kim Reynolds announced the creation of the Child Care Task Force in March, which was tasked with developing recommendations to address the child care crisis. She released the task force’s recommendations to the public in November.

Despite all those measures, child care advocates say much more is needed.

“We need money. … More and more center directors are going home crying every night not knowing if they’ll be able to open their doors the next day financially. If we lose any more child care centers in Linn County, we’re going to be hurting, bad,” Niemi said.

“My husband and I will joke, ‘There has to be a light at the end of this tunnel.’ And my husband, who is kind of a smart alec, says, ‘I think somebody needs to change the light bulb. … It burnt out,’ ” she said.

Banta said she wonders if the issue of child care has hit rock bottom yet.

“With child care and the number of women dropping out of the workforce, has it gotten so bad that we’re really willing to solve this problem once and for all?”

Editor’s note: Next week, we’ll be highlighting proposed solutions to the child care crisis by diving deep into the Child Care Task Force recommendations. Sign up for the Fearless newsletter to be among the first to read the story when it publishes.

2 Comments

Katherine Clark · January 12, 2022 at 11:49 pm

If the child care problem is so bad in Iowa, why did three out of four of our representatives in congress vote against child care legislation (Build Back Better)? It would have provided federal funding for our state.

John Carston · March 12, 2022 at 1:23 am

I love that you talked about the importance of having sufficient employees to teach children for the future. My neighbor mentioned to me that she plans to enroll her son in preschool and asked if I had any suggestions for the best preschool to consider. Thank you for your educational article, I’ll be sure to tell her that it’s much better if she contacts a reputable childcare center, as they can answer all of her questions while also providing high-quality education and memories for her son.

Comments are closed.