As told to Emily Kestel

Courageous Fire is a social entrepreneur and owner of Courageous Fire LLC, a company that educates the community about domestic violence, and the founding executive director of Courageous Access, a nonprofit that provides direct services to survivors of domestic violence.

The following story has been formatted to be entirely in her own words, and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This story mentions instances of domestic violence, and may be triggering to some. The National Domestic Violence Hotline is available at 800-799-7233.

I want to fight for my future, and I want to fight for the future of others.

I [changed my name to Courageous Fire because] I wanted to get away from what I felt when I heard my name [in my ex-husband’s] mouth. He would snarl or growl it. It got to the point where when it was time for me to introduce myself and I got ready to say that name, my stomach would get upset.

I said, “You know what, it’s time to leave that.” I wanted to pay homage to Andrea Kay, because she got me this far. I didn’t want my new name to completely ignore her existence. I looked at the meaning of my name, and Andrea meant courageous. Kay means fire, or fiery. I thought that was indicative of my journey.

I was in a marriage for 13 years without realizing that it was abusive. I watched the ABC after-school specials, and [domestic violence was seen as] a fist to the face. He didn’t do that. He did things that made it hard to move forward both as an individual and a family.

[At the beginning of our relationship], it was a typical white knight story. I was vulnerable, because I had some illnesses going on that he knew about. He was very kind, helpful and attentive. He was living in Omaha and was driving back and forth to see me. I thought, “He has no reason to drive back and forth unless he’s a good guy.” We ended up having two girls together.

So when he starts showing these things that are inconsistent [with who I thought he was], you just assume it’s unrelated. You think, “Maybe he’s just off at the moment. Maybe he’s had a bad day. Maybe he’s stressed about something.”

You keep feeling bad about certain things in your marriage, but you don’t know the language, so you can’t pin it on anything. You just know it doesn’t feel good.

You want your kids to have opportunities, you want them to feel good about who they are, you want to be able to start saving money for their future. He says he wants those same things, but he won’t go to work. When you go to work, he shows up [at your office] and he’s disruptive. You’re like, “OK, is he trying to make me lose my job?” Later on, you learn, that’s a form of financial abuse.

You realize that as a former prostitute when you were getting to know him, you told him some things. Now, in the bedroom, he tries to get you to do some of those things you did back then. “Well, if you could do it for them, you can do it for me. I’m your husband. I don’t get those things?” You realize that’s sexual coercion, that’s a form of domestic violence.

He takes your phone, goes through it and you get in trouble when you come home from work. You don’t realize that’s digital stalking, that’s domestic violence.

All the things about him that you thought were cool have become requirements. You must push my rap tape. You must push my jewelry. You must push my food. You must give up your tax returns every year for my next new great idea that I’ll give up on in a month.

Every time I tried to build something for our family to move forward, to get out of poverty, to get out of debt, he always had a brilliant idea that took the money.

I kept thinking it was because he came from an abusive background, and that he didn’t know how to handle himself in life and relationships, and he just needed my help, and the love of a good woman. You’re invested. So you say, “I’m going to be faithful to him until he gets back to himself.”

When my daughter was 12, we were in a bookstore and she saw a book about domestic violence. She said, “Mommy, I want this book.” It wasn’t until later that she told me, “I was lying, I didn’t want the book. I knew if I said I wanted it, you’d get it and read it.”

You don’t know that your life actually has labels of what you’re living through. Then you start putting the pieces together. I don’t have a better word than “unsettling” when you realize that you are in the middle of something you thought you knew, and it’s exactly the opposite of what you thought.

You think, “That’s why I’m so miserable. That’s why when I’m in the car, I think about taking off my seat belt, opening the door and letting the wind take me.”

[The moment it all changed was when] he wanted us to go on a trip [to his parents’ house] that we could not afford. We didn’t have money to eat for two weeks if we went on this trip. I told him, “You’re going to have to make $15 work [for groceries] when we get back. We cannot spend any money on this trip, you understand that, right? You can’t show off and cook for your family.”

The minute we get to his parents’ house, he tells everybody he’s going to cook. He has five siblings, they all have kids, and they’re all there. Their kids have kids, and they’re all there. He comes into a side room with me and looks at me [and asks for money]. I tell him there’s nothing I can do about it, so his mom pays for the groceries.

When we got back home, I told him he needed to go to the store, because in the morning, there’s not going to be anything to eat. He manufactures this huge argument which gives him a reason to be upset and offended, which then gives him a reason not to go to the store.

My mind clicked, and that was the moment I realized, “This is all this is ever going to be. He pouts to get his way, I go through hell to make it happen, it’s never enough, I get punished, my kids walk on eggshells until he decides it’s over, and then we do the whole thing over again.”

I got on the phone with the National Domestic Violence Hotline. I said, “Listen. I don’t know how to describe what I’m living in, but it feels like hell.” They said, “All right, can you tell me about it?” I started describing stuff, and I was so embarrassed. I said, “This probably doesn’t even make any sense to you.” They responded by naming almost every form of abuse from my verbal vomit. I felt validated at that moment.

Then they said, “Do you want to go somewhere? Do you want to take you and your kids and leave?” They sent me a cab and paid for it. I went to a shelter and had a conversation with somebody whose job it is to understand what you’re supposed to do.

That was the turning point for me, because it meant that I wasn’t crazy and something could be different for me and my kids. I started imagining what a future without all of this chaos could look like. It looked beautiful and promising.

I prayed that he would leave on his own. Two weeks later, he said, “I should remove myself.” He’d already called his sister and got money for a one-way bus ticket to Omaha.

After all of that, I realized that’s not just the story of Andrea, that’s the story of Black women. This is the national picture of what it’s like to be a Black woman in domestic violence. This can’t stay the same. We’re 2½ times more likely to be killed. What can I do that’s going to make this different for Black women?

[As it was happening,] my community was saying, “I don’t get it. He’s not hitting you, right? He’s not putting his hands on you, right? Why don’t you guys just work that out?” In the Black community, with the church narrative, the strong Black woman narrative, all of that makes it harder for us as Black women to get out of domestic violence.

We don’t tell people anything because we don’t want to be embarrassed for not being strong. We don’t want to be evil for not being holy enough to keep our marriage together. We don’t want the judgment, and we don’t want the divorce, because we know we’re not going to get that support. That’s a big part of why we don’t say anything. We know we will be looked at as a race-traitor.

How many other women are sitting around like this, confused and miserable, who think that this is just how their life has to go until they die? I need to help other women understand the lesser-known types of domestic violence. I have to do something to change that.

How am I going to impact the centers of must and the centers of trust – the places we have to go and the places we go because we feel safe? What am I going to do for all of these women like me? How do I help these women rebuild?

Domestic violence took my years, my hair, my finances, and even physical parts of my body that were sexually forced into that will forever be deformed and less functional. But [domestic violence] lost. Because I made it out.

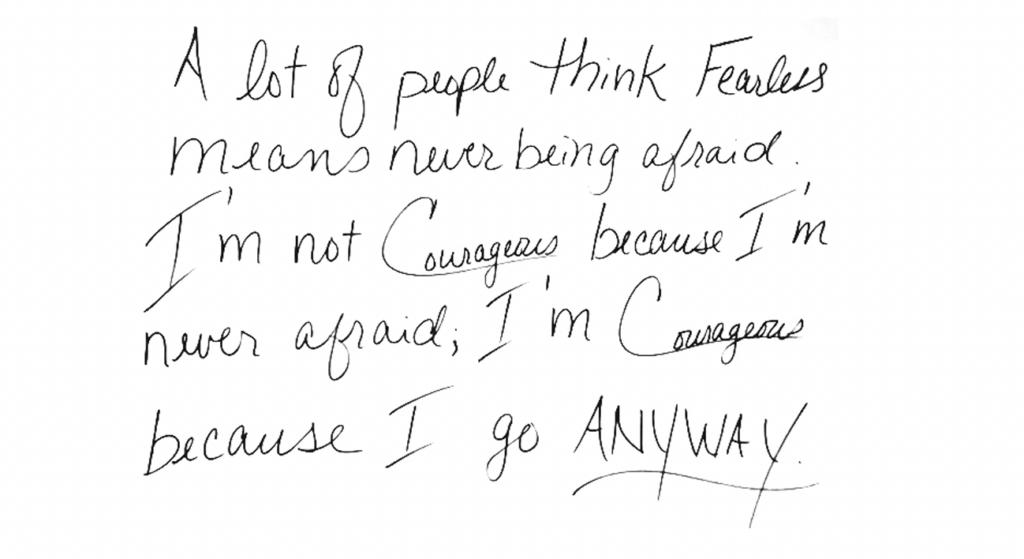

I don’t do this because it’s not scary; I do this because I refuse to accept anything less than what I deserve. I do it because at this point, I know nothing but building, claiming territory and knocking down barriers.